Artificial intelligence can be a powerful resource for overcoming accessibility barriers in the classroom, but it also can create or exacerbate those same accessibility issues.

“We see it both ways,” says Kate Sonka, Executive Director of Teach Access, an advocacy and professional development organization that promotes digital accessibility skills for the workplace.

“There are legitimate concerns about what sorts of ways AI is being used and how it might increase inequity, but we also have been hearing and seeing that AI could be used as an assistive technology. It’s an interesting thing to watch unfold, trying to parse through when and where we want to use it and how we want to use it.”

Teach Access supports instructors in educating their students about digital accessibility and in addressing the accessibility skills gap in the workforce. It was a relatively new organization — seven years into its work — when AI emerged in 2023 as a significant factor in technology accessibility.

When they began to focus on AI’s impact on accessibility in instruction, Sonka says, it discovered Every Learner Everywhere and its emphasis on equity in digital learning, and a new partnership was born.

The first shared project between the two organizations is a forthcoming report that aims to uncover the benefits and concerns of AI in accessibility instruction for educators and for the students they’re preparing for the workplace. Teach Access is developing the report as a toolkit for using artificial intelligence to enhance learning and overcome inequities in accessibility. Planned for early 2025, the document will explore AI’s impact on accessibility in a variety of ways from pedagogy to how it can be used as assistive technology.

The first shared project between the two organizations is a forthcoming report that aims to uncover the benefits and concerns of AI in accessibility instruction for educators and for the students they’re preparing for the workplace. Teach Access is developing the report as a toolkit for using artificial intelligence to enhance learning and overcome inequities in accessibility. Planned for early 2025, the document will explore AI’s impact on accessibility in a variety of ways from pedagogy to how it can be used as assistive technology.

“As we consider the various ways our students arrive and exist in our classrooms, as well as the instructors, and just what it means to have today’s learners in the classroom, it felt like a great space to collaborate,” Sonka says.

Enhancing employability

Working with educators, technology industry partners, disability advocacy organizations, and the public sector, Teach Access helps to foster learners’ interest in accessibility. The organization also encourages educators to teach the skills required to facilitate accessibility in the workplace.

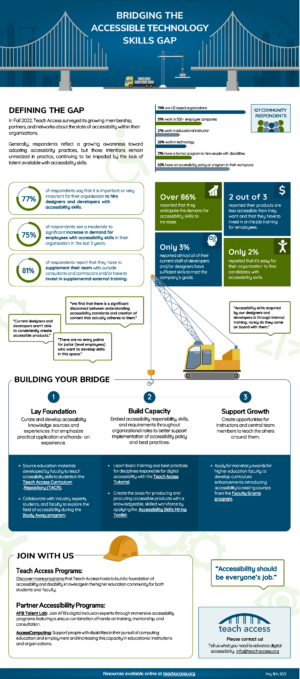

That emphasis on workforce preparation is important. More than 86 percent of Teach Access’s members surveyed in fall 2022 anticipated an increase in the demand for accessibility skills. Only 2 percent reported that their organization can easily find job candidates with those skills.

A recognition of the need for accessibility and the skills to help provide it can help job seekers qualify for roles in any sector. A software developer, for example, should be adept at creating tools to help those who cannot use a computer mouse to navigate an application. A marketing professional should understand how to create alt text that clearly identifies the contents of an online image for those with visual impairments.

“If we’re thinking about institutions wanting to create pathways, experiences, and opportunities for students to be successful once they graduate and leave our institutions,” says Sonka, “this is one of those pathways.”

Incorporating accessibility

The toolkit that Teach Access is partnering with Every Learner to develop will examine how AI is influencing the ways that instructors address the topic of accessibility. For some, that discussion might require 15 minutes of class time each week. For others, it might be a full module of lessons on the role of accessibility in a particular academic discipline.

“Even disability awareness in general, helping students understand that there are people with disabilities in this world and different ways that they interact with content and digital spaces, is a great place to start,” Sonka says.

Teach Access and Every Learner are also exploring ways to help prevent AI from perpetuating barriers to accessibility and equity. An instructor developing a lesson might use AI to generate text that introduces complex concepts, for example. Because AI provides text based on existing online content, the language might not be clear enough to be accessible for all learners.

“If you’re thinking about something like the carbon cycle and asking ChatGPT about it, you could continue to prompt it to use plain language,” says Sonka. “Then you get it down to the space where it’s easier to wrap your head around a concept of this level.”

While the Web Accessibility Initiative’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines site is an industry standard, Sonka says, its technical language may be overwhelming for faculty trying to make digital learning more accessible for their students. Instead, in addition to the forthcoming toolkit from Teach Access and Every Learner, she recommends that instructors and administrators refer to the resources on Teach Access and WebAIM for training, tools, and inspiration.

This exploration is vital, Sonka says, because of the long-term importance of AI and its impact on accessibility.

“We will always be thinking about accessibility,” she says. “And this really feels like a moment where AI is in the public consciousness in a way that will be here for a while. Both of these are topics we should be paying attention to.”

Subscribe to our newsletter to learn about new publications and professional development opportunities